Stress-Related Illness

Stress is an intense physical and/or emotional response to a difficult or painful experience. Stressful events can range from taking a test in school to dealing with a loved one's death. Reacting to such events, the body's stress response system can cause a rapid heartbeat, a rise in blood pressure, and other physical changes. Stress-related illnesses are physical or mental problems that sometimes seem to be brought on by or made worse by stress. They can include headaches, stomachaches, sleeplessness, depression, anxiety, and many other conditions.

KEYWORDS

for searching the Internet and other reference sources

Cortisol

Epinephrine

Hypothalamus

Stress Is Not All in the Head

Imagine Alicia, the goalie on the traveling soccer team, with the opposing team barreling toward her with the ball in possession. Imagine Eduardo at 7:59 a.m., running for the school bus that leaves at 8:00 a.m. Imagine Maria, whose dog has just been run over by a car. Anyone who has been in situations such as these knows what stress feels like: The pulse quickens, the heart races, breathing becomes heavier, and muscles tense. Some people feel nauseated and start to sweat. Others freeze and feel a sense of dread.

* hormone is a chemical that is produced by different glands in the body. A hormone is like the body's ambassador: it is created in one place but is sent through the body to have specific regulatory effects in different places.

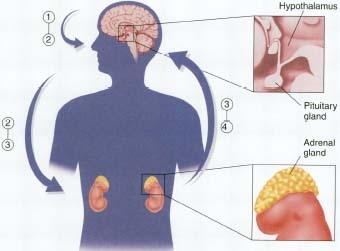

The stress response

All these changes in the body happen because stress sets off an alarm in the brain. This alarm triggers the release of hormones * , which trigger the release of oxygen and glucose, which send emergency energy to the brain and muscles. This is called the "fight or flight" response because it prepares the body to fight or run.

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that produces hormones. When the stress response begins, the hypothalamus sends a hormone called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) to the pituitary gland, which then sends a hormone called adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands. The adrenal glands produce cortisol (in response to ACTH) and epinephrine (in response to signals sent from the brain through the nervous system), which help the body produce emergency energy and support the "fight or flight" response. As long as the brain perceives stress, it continues to produce CRF. The body's stress response ends when the brain relaxes, allowing hormone levels to return to normal. Scientists think the "fight or flight" response developed because it helped primitive humans deal with such threats as attacks by wild animals. In many cases, the stress response is still helpful—it may help Alicia react more quickly to block the ball and Eduardo race to the bus stop in time. And a certain amount of stress helps keep life exciting and challenging. But in other cases, like Maria's grief over her dog, the natural stress response may not be helpful at all.

Chronic stress

Events that trigger the stress response usually do not last for very long. When long-term problems with school or family or illness create chronic * stress, however, they keep the body's stress response system activated over too long a period of time. This can contribute to many psychological disorders. Doctors think it also can lead to physical problems, such as chest pain, headaches, and upset stomach. Researchers suspect that, over time, high stress levels can contribute to more serious illnesses, such as high blood pressure and heart disease. They also suspect that chronic stress may suppress the immune system, the body's natural defense against infection, leaving people more prone to illness, perhaps even to some forms of cancer. Much work must still be done, however, to determine whether those suspected links are real and to unravel the complex relationships between physical and psychological factors in health.

* chronic (KRON-ik) means continuing for a long period of time.

Stress and Neglect

Research using animals suggests that neglect early in life can cause animals to respond more intensely to stress when they grow up. In one study, researchers compared two sets of rat pups: Group A rats were removed from their mothers for 15 minutes a day, while Group B rats were separated for 3 hours.

When the pups were returned to their rat mothers, the mothers tended to respond differently: After 15-minute separations, the rat mothers intensively licked and groomed their returned pups. After 3-hour separations, the rat mothers ignored the pups, at least at first. In subsequent tests, the "neglected" pups in Group B were shown to respond to stress more intensively than the Group A pups. This response appeared to last into adulthood.

Another study reported that infant monkeys whose mothers had difficulty providing them with food had higher levels of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), one of the key hormones in the stress response. Because the monkey mothers were distressed about finding food, they behaved inconsistently toward their offspring, sometimes neglecting them. These young monkeys were more anxious than usual when confronted with separation or new environments; in other words, their stress response was more intense. "Stressing out" these animals as babies seemed to shape the way their brains and nervous systems responded to stress when they grew up.

Which Illnesses Are Stress-Related?

It is hard for researchers to establish a definite cause and effect relationship between stress and specific physical symptoms or illnesses. Not only do people's minds and bodies react differently to stress, but there also are other factors at work when someone gets sick. The following conditions are known or believed to be stress-related (as opposed to stress-caused):

- Pain caused by muscular problems, such as tension headaches, back pain, jaw pain, and repetitive stress syndrome. Pain of many kinds seems to be caused or made worse by stress.

- Gastrointestinal (gas-tro-in-TES-ti-nal) problems, such as heart-burn, stomach pain, and diarrhea.

- Insomnia, or difficulty sleeping.

- Substance abuse, including smoking, drug addiction, and heavy drinking of alcohol. Substance abuse, in turn, can lead to other ill-nesses, including heart disease and cancer.

- Asthma attacks in people who already have the condition or who are susceptible to it.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder, a mental disorder in which people repeatedly relive a terrifying experience in dreams and memories long after the event has passed; and acute stress disorder, in which they have similar symptoms immediately after the event.

- Other mental disorders, including eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and possibly schizophrenia.

- Cardiovascular (car-dee-o-VAS-kyu-lar) problems, such as irregular heartbeat, hardening of the arteries, and heart attack. Stress makes the heart beat more quickly and increases blood pressure temporarily. Although long-term effects have not been proven, many scientists suspect that they exist.

The Mind-Body Connection

Why do scientists believe that stress plays a role in causing illness? Although they still are unraveling the complex relationship between physical and psychological health, many studies suggest links between stress, illness, and the immune system's ability to fight off illness. Some examples:

Studies have found that people who recently lost a husband, wife, or other loved one—which causes intense stress—are more likely to die themselves, from a wide variety of causes.

Workers who reported high levels of stress were estimated to incur nearly 50 percent more in health care expenditures.

Researchers reported that two groups of people under stress—medical students taking exams and people caring for Alzheimer's disease patients—showed decreases in their immune system activity.

Support Groups and

Stress Reduction

When people are diagnosed with illnesses such as cancer or AIDS, they usually take powerful drugs that can reverse or slow down the biological processes of the disease. Studies suggest that patients also benefit by joining support groups. Social relationships are believed to increase feelings of well-being and to reduce stress.

In the 1970s, a psychiatrist in California led support groups for women with advanced breast cancer. Group members expressed their emotions and concerns during regular meetings. A decade later, the same psychiatrist went back and reviewed the women's records. He found that the women who participated in the support groups survived twice as long as similar patients who did not.

In a later study, another California psychiatrist concluded that group therapy was helpful to people diagnosed with a serious form of skin cancer. Those who participated in the support group were found to have greater numbers of active tumor-killing cells than patients who did not.

A researcher at the University of Miami completed a similar study with men who tested positive for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Men who were trained in stress-management showed a slower rate of decline in the immune system cells that the virus attacks, compared to those who did not. More work remains to be done, but these and other studies suggest that support groups can have an important effect on the body's ability to fight off disease.

Learning to Deal with Stress

Stress is inevitable, but people can learn how to cope with it. Doctors sometimes suggest the following strategies for managing stress:

- Exercising takes the mind off stressful thoughts, and causes the release of chemicals called endorphins (en-DOR-fins) in the brain that provide feelings of calmness and well-being.

- Making time for hobbies and enjoyable activities outside school and work can decrease stress levels.

- Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, visualizing pleasant images, meditation, and yoga can lower the heart rate and blood pressure while reducing muscle tension.

- Scaling back on activities and responsibilities and managing one's time effectively can head off stress-causing situations.

- Participating in support groups or sessions with professionally trained counselors or psychologists can help provide an outlet for emotional stresses.

Using drugs, alcohol, and smoking to cope with stress can make stress-related problems and illnesses worse.

Relaxation Meditation

Many people find that relaxation meditation is a good way to relieve some of the stresses of everyday life. People who meditate regularly recommend the following:

- Finding a quiet room or place away from disturbances.

- Sitting in a comfortable position with the spine straight.

- Repeating a special word or phrase throughout the session.

- Keeping eyes closed or eyes focused on an object.

- Clearing the mind of distracting thoughts, repeating the chosen phrase, and concentrating on the chosen point of focus.

See also

Alcoholism

Anxiety Disorders

Asthma

Cancer

Depressive Disorders

Eating Disorders

Heart Disease

Hypertension

Insomnia

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Repetitive Stress Syndrome

Substance Abuse

Temporomandibular Joint Syndrome

Trauma

Resources

U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health,

6001 Executive Boulevard, Room 8184, MSC 9663, Bethesda, MD 20892-9663.

Telephone 301-443-4513

http://www.nimh.nih.gov

American Psychological Association (APA), 750 First Street N.E.,

Washington, D.C. 20002-4242. The APAs on-line Help Center features

useful information about the stress-illness connection.

Telephone 202-336-5500

http://helping.apa.org

KidsHealth.org

from the Nemours Foundation posts fact sheets that spotlight stress in

children and in teenagers.

http://www.kidshealth.org/teen/bodymind/stress.html

American Institute of Stress, 124 Park Avenue, Yonkers, NY 10703.

Telephone 914-963-1200

http://www.stress.org

National Mental Health Association, 1021 Prince Street, Alexandria, VA

22314.

Telephone 800-969-6642

http://www.nmha.org

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: