Bacterial Infections

Bacterial infections are illnesses that occur when harmful forms of bacteria multiply inside the body. They range from mild to severe. Although they include such deadly diseases as plague, tuberculosis, and cholera, these and many other bacterial infections can be prevented by good sanitation or cured by antibiotics.

KEYWORDS

for searching the Internet and other reference sources

Antibiotics

Antibiotic resistance

Bacteriology

Drug resistance

Infection

Bacteria are everywhere: in soil, in water, in air, and in the bodies of every person and animal. These microorganisms * are among the most numerous forms of life on Earth.

Most bacteria are either harmless, or helpful, or even essential to life. Bacteria break down (decompose) dead plants and animals. This allows chemical elements like carbon to return to the earth to be used again. In addition, some bacteria help plants get nitrogen. Without them, plants could not grow. In the human body, bacteria help keep the digestive tract working properly.

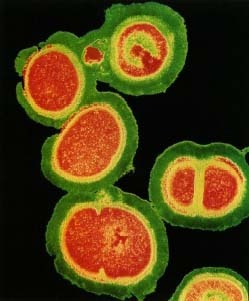

Like viruses, however, bacteria can cause hundreds of illnesses. Some bacterial infections are common in childhood, such as strep throat and ear infections. Others cause major diseases, such as tuberculosis, plague, syphilis, and cholera. The infection may be localized (limited to a small area), as when a surgical wound gets infected with a bacterium called Staphy loco ccus (staf-i-lo-KOK-us). It may involve an internal organ, as in bacterial pneumonia (infection of the lungs) or bacterial meningitis (infection of the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord).

* microorganisms are living organisms that can only be seen using a microscope. Examples of microorganisms are bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Some bacteria, such as pneumococcus (noo-mo-KOK-us), which is also called Streptococcus pneumoniae, almost always cause illness if they get into the body. Others, such as Escherichia coli, usually called by the short form E. coli, often are present without doing harm. If the immune system is weakened, however, these bacteria can grow out of control and start doing damage. Such illnesses are called "opportunistic infections." They have become more common in recent years, in part because AIDS, organ transplants, and other medical treatments have left more people living with weakened immune systems.

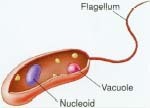

How Are Bacteria Different?

Unlike other living cells, bacteria do not have a membrane enclosing their nucleus, the part of the cell containing DNA, or genetic matter. Unlike viruses, most bacteria are complete cells that can reproduce on their own without having to invade a plant or animal cell. Some bacteria, however, do need to live inside another cell just as viruses do.

How do bacterial infections spread?

Different bacteria spread in different ways. Examples include:

- through contaminated water (cholera and typhoid fever)

- through contaminated food (botulism, E coli food poisoning, salmonella food poisoning)

- through sexual contact (syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia)

- through the air, when infected people sneeze or cough (tuberculosis)

- through contact with animals (anthrax, cat scratch disease)

- through touching infected people (strep throat)

- from one part of the body, where they are harmless, to another part, where they cause illness (as when E coli spread from the intestines to the urinary tract).

How do bacteria cause illness?

Bacteria can cause illness in several ways. Some destroy tissue directly. Some become so numerous that the body cannot work normally. And some produce toxins (poisons) that kill cells. Exotoxins are poisons released by live bacteria. Endotoxins are poisons released when the bacteria die.

How Are Bacterial Infections Diagnosed and Treated?

Symptoms of bacterial infections vary widely but often include fever.

Diagnosis

Doctors may test the blood, sputum, or urine for evidence of harmful bacteria. If a lung infection is suspected, the doctor may take a chest x-ray or do a biopsy, taking cells from an infected area to be examined. If meningitis is suspected, the doctor may do a spinal tap, using a needle to extract a sample of the spinal fluid surrounding the spinal cord for testing.

Food Poisoning

Food poisoning is often the result of bacterial contamination. Important precautions for preventing food poisoning include:

- Avoiding raw or undercooked meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs.

- Avoiding non-pasteurized dairy products.

- Throwing out food items that are old or have an "off" smell.

- Keeping foods cold until ready to serve.

- Storing and cooking foods properly.

- Washing knives, cutting boards, cooking utensils, and food preparation areas after every use.

- Washing hands before preparing food, before eating, and after using the bathroom.

Treatment

Most bacterial infections can be cured by antibiotic drugs, which were one of the great medical success stories of the twentieth century. These drugs either kill the bacteria or prevent them from reproducing. Penicillin, the first antibiotic, is still used to treat some infections.

Other widely used antibiotics include amoxicillin, bacitracin, erythromycin, cephalosporins, fluroquinolones, and tetracycline. Sometimes antitoxins are also given to counter the effects of bacterial toxins, as in the case of tetanus or botulism.

How Are Bacterial Infections Prevented?

Young children commonly get shots of vaccine to prevent diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, and Hemophilus influenza B, all bacterial infections. In addition, vaccines are available to help prevent cholera, meningococcal and pneumococcal infections, plague, and typhoid fever.

For many bacterial infections, good living conditions are the best prevention. That means clean water supplies, sanitary disposal of human waste, well-ventilated housing that is not overcrowded, and prompt medical treatment for people who do get sick.

Other steps include:

- Washing hands (before handling food; after using the toilet; after touching animals; after having contact with infected people).

- Washing fruits and vegetables before eating.

- Cooking meat thoroughly.

- Abstaining from sexual contact, or using condoms during sexual activity.

How Do Bacteria Become Drug Resistant?

Each kind of bacteria can be killed by certain antibiotics and each kind is naturally resistant to others. But in recent years, some bacteria have developed resistance to antibiotics that used to kill them. This is one of the big problems in controlling infectious diseases.

How does resistance occur?

In some cases, it occurs by chance. As bacteria reproduce, mutations (variations) in their genes occur all the time. One of these mutations may happen, by chance, to make one bacterium in a person's body less vulnerable to a drug. This bacterium multiples along with other bacteria. While other bacteria are killed off by the drug, the mutated—or resistant—bacterium thrives, and eventually spreads from person to person.

Flesh-Eating Bacteria

A virulent strain of Streptococcus A bacteria caused illness in 117 people in Texas between December 1997 and March 1998. Of those 117 infections, 26 (17 adults and 9 children) resulted in deaths. Described in media coverage as "flesheating bacteria," these pathogens caused their damage through a process called hemolysis (he-MOL-y-sis), which causes red blood cells to disintegrate. The Texas outbreak was short lived, and experts still do not know how it started.

Why does resistance occur more often now?

Humans can make drug resistance far more likely to develop than it would simply by chance. They do this when they use antibiotics that are not needed or when they do need antibiotics but stop taking them too soon.

Here is how those practices can increase resistance: Let us say that a man has a bacterial infection. He takes an antibiotic, feels better, and stops taking the drug in five days, even though the doctor said to take it for 10 days. Inside the man's body, the drug may have killed, say, 80 percent of the bacteria. That was enough to make the man feel better. But the bacteria still alive are the 20 percent that were toughest, the ones best able to survive the drug. If the man had kept taking the antibiotic, the toughest bacteria might have been killed on Day 8, 9, or 10. But now, left alone, they start to multiply. Soon the person feels sick again. But this time, all the bacteria in his body are the tougher kind. A scientist would say the person's behavior "selected" the most resistant bacteria for survival.

A similar process occurs when doctors prescribe antibiotics that are not needed. Let us say that a girl has a cough and fever. The doctor prescribes antibiotics on the chance that the girl has a bacterial infection. But she actually has a virus, and viruses cannot be treated with antibiotics. The girl's immune system, her natural defense system, fights off the virus as it would have without the drug. Meanwhile, the antibiotic kills off some bacteria that usually live harmlessly in the girl's throat. The bacteria in her throat that survive are those that are better at resisting the antibiotic. Later, if those bacteria get into her ears, her lungs, or some other part of her body where they can cause illness, the antibiotic may not work as well against them.

If events like these happen countless times, in countless people, eventually strains of bacteria may arise that partially or completely resist a drug that used to kill them.

See also

Botulism

Campylobacteriosis

Cat Scratch Disease

Cholera

Chlamydial Infections

Diphtheria

Ear Infections

Endocarditis

Food Poisoning

Gonorrhea

Legionnaire's Disease

Leprosy

Lyme Disease

Meningitis

Osteomyelitis

Peptic Ulcer

Plague

Pneumonia

Rheumatic Fever

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Salmonellosis

Strep Throat

Syphilis

Tetanus

Toxic Shock Syndrome

Typhoid Fever

Tuberculosis

Typhus

Whooping Cough

Zoonoses

Resources

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC posts a fact

sheet called

Bacterial Diseases

at its website.

http://www.cdc.gov/health/diseases.htm

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA posts a

Bad Bug Book

at its website that offers fact sheets about many different pathogenic

bacteria.

http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~mow/intro.html

Do different infections have different outcomes ? Such as staf for example? I think that's contagious for 86 days after diognosis?